ALTADENA, Calif. — Smoke from the ravenous Eaton Fire had barely cleared when signs began popping up on the charred remains of destroyed homes declaring Altadena was not for sale.

But one month after the wildfire consumed more than 9,400 residences and 14,000 acres in the foothill community north of downtown Los Angeles, the first vacant lot sold for $550,000 cash, $100,000 above the asking price.

Of the 14 properties that have sold to date in fire-ravaged Altadena, at least seven were purchased by developers or investors, including several from outside the U.S., according to a list provided by Jasmin Shupper, founder and president of the nonprofit Greenline Housing Foundation. They were all cash offers, she said.

Housing experts and community members worry the fierce competition could push out longtime residents who want to bring back Altadena’s small-town flavor and diverse enclaves but see that vision slip away as buyers with deep pockets and little historical understanding of the area swoop in.

“In our opinion, money isn’t everything and it never will be,” said Darrell Carr, whose Altadena home burned in the fire. “It’s the character of the people.”

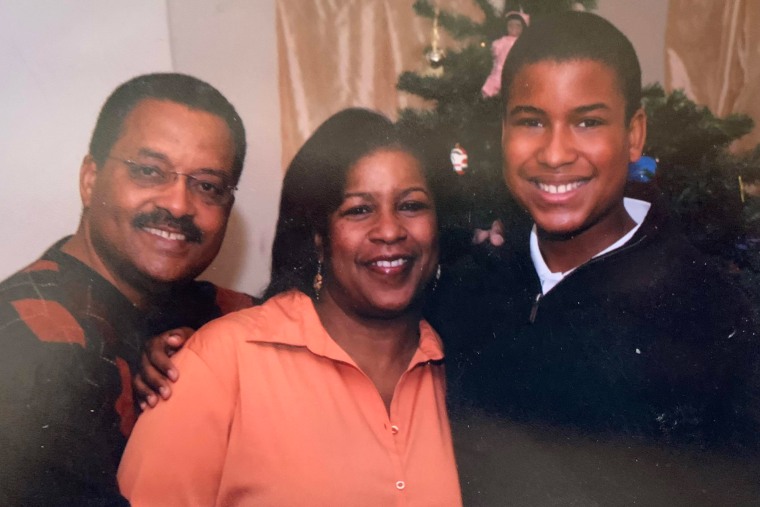

A family portrait of Darrell, Susan and Justin Carr.Courtesy Susan Toler Carr

A family portrait of Darrell, Susan and Justin Carr.Courtesy Susan Toler Carr

“We’re just afraid that we’ll see a bunch of cookie cutters go up and we’ll get a bunch of people coming and going and coming and going and we’ll lose the charm of Altadena.”

To counter this possibility, Greenline began securing long-term, temporary housing for displaced Altadena residents and entering into talks to purchase their burned lots.

Greenline closed on a property for $520,000 earlier this month and is in discussions with a handful of other sellers, Shupper said. The foundation has effectively become a “land bank,” which Pasadena-based lawyer Remy De La Peza describes as a space for immediate and urgent acquisition of land to prevent sales to private corporate interests.

Land banks have been established in cities like Atlanta, St. Louis and Cleveland to develop vacant urban lots for use by local nonprofits, community organizations and affordable housing.

“It’s holding on to land within the bank to buy us time to think about what we want Altadena to look like,” De La Peza said.

Deciding whether to rebuild is a difficult next step for families grieving the loss of their soulful neighborhood. Many want Altadena to remain the same quirky enclave that attracted artists’ studios, small horse ranches and mom-and-pop stores.

Before the January fire laid waste to much of Altadena, the neighborhood of some 42,000 people was a diverse haven for creatives and those who could not afford to buy homes in other parts of Los Angeles. It was one of the few areas in L.A. County exempt from redlining during the Civil Rights era, giving Black people a rare opportunity to own homes and build generational wealth.

People of color comprised more than half of Altadena’s population, with Latinos making up 27% and Black Americans 18%. The Black homeownership rate in Altadena exceeded 80%, almost double the national rate.

More than 60% of Black households were located within the burn area, compared to 50% of non-Black households, according to a UCLA study of the fire’s impact. Nearly half of Altadena’s Black households were destroyed or sustained major damage, compared to 37% for non-Black households.

“Policymakers and relief organizations must act swiftly to protect the legacy and future of this historic community,” said Lorrie Frasure, a professor of political science and African American studies at UCLA and one of the study’s authors.

The housing market, which was already out of reach for many residents, appears to be showing signs of topping pre-fire prices. From 2019 to 2023, the median home price in Altadena was more than $1 million, according to Realtor.com, and the median income was $129,123, according to the U.S. census.

Brock Harris, a local realtor who sold the first Altadena property after the Eaton Fire, expects new home sales to near but not exceed $2 million. He received dozens of cash offers for the first listing and now has five more listings, three of which are in escrow. They all have been cash offers. Prices have settled between $500,000 and $600,000, which is about 50% to 60% of what they were before the fire, he said.

“It’s purely financial,” Harris said of the people choosing to sell.

Rebuilding, he added, is an enormously expensive enterprise: “People have jobs and kids in school and lives they need to go on with. Is that a doable project for most people?”

When Carr and his wife, Susan Toler Carr, first visited the remains of their historic Spanish-style home, neither could imagine returning. Most of their neighborhood was reduced to rubble and the house they shared for 25 years was damaged beyond repair. Little of the structure remained, but what did reminded them of their late son, Justin, who died in 2013 at age 16 during swimming practice.

The Carrs were moved that a gate dedicated to their son, Justin, remained intact after the fire.Courtesy Amber Denker

The Carrs were moved that a gate dedicated to their son, Justin, remained intact after the fire.Courtesy Amber Denker

As the days wore on, it was those memories that convinced the couple to rebuild. But not all of their neighbors were convinced. Some have small children and are worried about the toxic environment, Carr said.

“It’s just a lot to think about,” Toler Carr added.

Altadena resident and realtor Michael Farah, whose home survived but was badly damaged by smoke, has seen his neighbors grapple with the question of whether to rebuild or sell. A neighbor who purchased his home in 2023 recently sold his vacant lot for $400,000 over the asking price in cash. It was in escrow for just 10 days.

Farah said his neighbor considered rebuilding, but the cost of using fireproof materials, like concrete and steel, was the deciding factor.

“The estimates just kept going up and up,” Farah said. “It was the best thing for him and his family just to move on.”

Ali Pearl, a University of Southern California writing professor who lost her home in the Eaton Fire, said she is committed to staying in Altadena. But her insurance payouts totaled $600,000 and builders are quoting her $1.2 million to rebuild.

“We bought that house with the intention of living there for the rest of our lives and passing that house down to our children,” she said, adding that she and her husband are applying for disaster loans to bridge the gap.

Through her work with the community group Altagether, Pearl coordinates resources and information for neighbors looking for alternatives to selling to developers. She sends them to Greenline in hopes of matching land to community members who have been priced out of Altadena.

“I think about my neighbors’ kids who were born and raised on my street, and how they have not ever been able to afford to come back to the neighborhood, who talk about how great that would be to live in Altadena again,” Pearl said.